This is an archive page. What you are looking at was posted sometime between 2000 and 2014. For more recent material, see the main blog at https://laboratorium.net

The Laboratorium

June 2001

I'm not quite sure how they've done it, but the Czechs have done pretty well at hanging on to their historic documents. They've got the founding charter of Charles University and the Declaration of the Estates of Bohemia, with the original seals. The latter is especially impressive, since there wasn't room enough on the Declaration itself for all the seals, so they tore the bottom into little strips and each noble affixed his seal to one of the strips.

The best, though, is one particular imperal decree for religous toleration. It's in several pieces in the display case -- because a later Habsburg emperor publicly tore it up as part of his campaign of re-Catholicization.

While travelling, I am using a Hotmail account for emergencz contact purposes; everz few dazs we find an Internet cafe and check in. In Austria, this meant free roadside kiosks, although we usuallz had to wait in line behind Viennese teens sending SMS messages. In Hungarz, we need to paz, but not much: usuallz around 10 forints a minute -- that is, two bucks an hour. The onlz trickz part is the Hungarian kezboards, which swap 'y' and 'z.'

One daz, we go to a different place than we usuallz do and I find mzself unable to log into Hotmail. Javascript is diabled in the browser, without which the stupid Microsoft web site will not work. But this is a problem I can handle, even in a Hungarian version of Internet Explorer with menus in Hungarian: I can find mz waz to the securitz settings page without much trouble, which is a sign, I suppose, that I know IE a little too well.

Once there, however, I can't figure out which of the several hundred toggles controls JavaScript in pages, so I take the nuclear approach and disable all securitz checks for the Internet yone, something I can do bz clicking on the little globe icon and then dragging the slider to the bottom of the scale. Poor user securitz transcends all national and linguistic barriers.

After ditching my airplane-reading detective thriller in the room in Vienna, I've been reading Anne Fadiman's excellent The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, about tragic cross-cultural misunderstanding in the case of an epileptic Hmong child in California. One of the book's central themes is the way in which the communications barriers between her parents and her doctors manage to infantilize all involved -- something I'm acutely conscious of in Hungary, a country with a non Indo-European language.

It's not that we're unable to communicate with Hungarians, but rather that we come across as idiots. We decided early on to do our best not to perpetuate the stereotype of ugly Americans who shout all the time, so we're humble, and polite, and wholly inarticulate. It's not just the language: we don't know the customs that even small children know, and thus we come across as infants. [Quite literally, I think: our most successful social interactions are making funny faces at the adorable children on the subway.]

For example, pretty much all my life, I've "learned" that when counting on my fingers, I should start with the forefinger for "one," add the middle finger for "two," and so on, throwing in the thumb only for "five." Well, in pretty much all of Eastern Europe, one starts with the thumb for "one," adding the forefinger for "two" and proceeding along the hand in order. This takes us a few days to notice -- until Sarah pieces together all the strange looks and loud sighs we've gotten every time we asked for "one" pastry or "one" bus ticket with some incomprehensible hand gesture.

After the quiet of Visegrad and Bratislava, the waves of people in Prague are an unpleasant change. I have a strong desire to strike out with my fists, landing blows left and right on random passers-by. The worst are the hordes of loud and drunken British hoodlums on holiday, drinking beers and leering at women.

In the train station, there are a pair of uniformed police officers passing out little cards, warning that "When democracy came to Prague it was unfortunately accompanied by the inevitable surge in crime." (Which, when you think about it, raises more questions than it answers.)

On our first metro trip, a couple comes to a halt directly in the doors of the train, looking so thoroughly out of it as to be incapable even of befuddlement. Inside the train, a fat and sweaty hostel-monger leans over to us conspiratorially. "Romanians," he says, "They do it so you'll push up and they can feel for your wallet." Two stops later, Sarah, pointing out that he left the train following two young and female backpackers, pronounces him even sketchier than the pickpockets.

The flight over is a mixed bag. On the one hand, they show Proof of Life. Not only is it a bad movie with a paramilitary fetish, it's also the same bad movie with a paramilitary fetish they showed on the last plane flight I took. On the other hand, they also show an episode of that Animal Planet show with the crazy Australian guy, in which he systematically pokes, prods, and otherwise provokes the deadliest snakes on the planet. One of them, displaying an almost vaudevillian sense of comedic timing, bites him. Much hilarity ensues.

In front of me is a family of six; one of the kids trips a flight attendant carrying a full tray of drinks. Her ferocious "Watch where you put your feet, please!" is priceless.

For me, it's been two red-eye flights in three days, on neither of which have I been able to sleep more than a couple of hours. We hit the ground running in Vienna, and in some kind of minor miracle, wake up the next day wholly adjusted to Central European Time.

Visegrad Castle is a good half hour's hike uphill from the Danube. Its impressively large walls provide some incredible views of the surrounding river valley (you see immediately why they put the castle here), and also contain the first of no fewer than three torture museums we encounter on our trip.

Just up the ridge from the castle -- past the parking lot and hilltop hotel -- is a "summer toboggan," something I'd previously encountered only on vacation trips to the Alpine Slide in Vermont. This one is a bit lower-rent -- the track is metal instead of concrete, and the sledders ram each other worryingly often -- but otherwise, it's a perfect bit of nostalgia, a bolt from the blue.

I'd never thought of Vienna University as a party school.

Interesting sidenote: in 1420 and 1421, Vienna's Jewish community was wiped out in an especially bloody pogrom. The stones from the synagogue were then used in the construction of the University.

While walking around Prague, we hear "Yesterday" being performed by street musicians at least five times, including flute, guitar, and accordion versions.

Once again, we have no clue.

Of all cities in the world, there is none so closely identified with Mahler as Vienna -- he was conductor of the Court Opera here, and it was here that he wrote much of his most famous music -- but you'd never know it to visit Vienna. The guys in the wigs and breeches -- with whom I am obsessed -- are all Mozart Mozart Mozart and Strauss Strauss Strauss, and so are all the gift shops, even at the Opera House itself. Not even on Mahlerstrasse can one find any Mahler tchotchkes. Where are the Mahlerkugel? Nowhere to be found.

We go to a concert, but due to my ignorance of German and of the Konzerthaus floorplan, I wind up in the wrong seat. About five minutes later, there is a Catholic churchman -- I don't know my ranks and insignia, but he looks pretty impressive -- glowering down at me. He examines my ticket, and sends me packing, because the Regierungsloge, as he dismissively explains, is one of the boxes on the sides, rather than the regular seating at the back. Were this the Middle Ages, I have no doubt that he'd find a way to send me to the stake: he has the scowling face for it.

To borrow one of Sarah's phrases, the concert -- Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducting Handel's Israel in Egypt -- is the musical equivalent of the pictures of Jesus we've been seeing: technically perfect, historical as all get-out, about twice as long as it needs to be, and exquisitely boring except in the big finale and a couple of other nice bits. Also, "keine pause" is not the same as "kleine pause," as we learn when the expected intermission turns out to be just a retuning break for the orchestra.

After a couple days here, the Habsburg pattern is becoming clear. Build a huge honking palace, put up some gardens behind it, then put up another palace at the other end of the garden, since you're sure to be exhausted by the time you've walked that far.

Budapest's Great Synagogue is an odd building: it has the ground plan of a Protestant church, but the ornamentation is wholly Moorish. As we are walking through the memorial garden, it strikes me that they killed the Jews here, too. I knew about the Nazi program of evil before, of course, but the history of the Holocaust has a more immediate impact when you are confronted by the geography of genocide: they came for the Jews here and here and everywhere.

Having finished the Fadiman, I decide to read books that relate to our travels, so Eichmann in Jerusalem seems a reasonable place to start. I pay through the nose for a copy -- it seems especially expensive, given that one can eat like a king for four or five dollars -- and it sets a tone for the rest of the trip. Little omissions leap out at me: the Slovaks seem unwilling to admit the that they cut a deal with the Nazis to gain an "autonomous" Slovakia. But it also contextualizes things, and displays like a contemporary rail-link map of the deportations from Hungary to the camps are rendered that much more chilling.

I have a Big Thought a few days later, one of -- I promise -- fairly few during the trip: the followers are more interesting, more important, than the leaders. The great majority of people are capable of great collective courage, or of perpetuating the utmost evil. Why the one and not the other, that's what matters, and the leaders matter not for their own strange psychology, but for their effect on the more familiar psychology of the great Us.

Visegrad is unbelievably peaceful. Our room has a balcony with a view of the fortress; we spend an entire day sitting on it, reading and listening to a nearby brook and the ducks who waddle along its banks.

Eevery time you need to go an airport, take a week off your life expectancy.

My flight is four hours late, the next flight to Frankfurt turns out not to exist ("I know the computer shows that flight, but it shouldn't."), and there is an unpleasant episode when I need to run from one terminal of the airport to another -- with my travelling-in-Europe backpack on my back, of course.

I wind up having to deal with six different airline employees, and by the time they have sorted out the unexpected problems my innocuous-seeming reservation poses, the actual "ticket" they issue me consists of two handwritten sheets of paper. Free airline travel for life can't be as simple as stealing the special pad of paper on which these "tickets" have been written, can it?

Buda Castle Hill is home to ancient limestone caves. Over the centuries, Budapest's various rulers carved out chambers from the rock, putting together a reasonably substantial network of passages. Now, surprise surprise, they're a tourist attraction.

When it comes to the lowest common tourist denominator, this is one of those divisions by zero. They've loaded up the "Labyrinth" with humanesque statues meant to seem ominous, piped-in sound effects, and an especially cheesy exhibit of "recently excavated ancient fossils" featuring the imprints of computer keyboards, ATM terminals, and Coke bottles. The whole is so busy trying to be atmospheric that it's almost entirely uninteresting.

There's a bunch of schoolkids down there with us, though, running around trying to scare each other and generally making an astonishing racket. I convince Sarah to pretend that the kids are actually a pack of bloodthirsty ape-men hunting us with crude stone hand-axes, and we are careful to hide behind pillars whenever the ape-men go by. The Labyrinth winds up being worth the trip.

This building, the Summer Palace of Prague Castle, is the most authentic Renaissance belvedere outside of Italy. During our visit, the Castle is hosting a Czech architecture exhibit: each part of the show, from Romanesque to present-day, is housed in an architecturally appropriate part of the Castle.

According to our multi-lingual map, in French, the Cathedral of St. Vitus is rendered as Cathedrale St-Guy. We have no idea, either.

By whatever name, it's exquisite, especially the modern stained glass. Just don't go up the tower if you have medical issues. Have a heart attack up there and you're a goner. There are almost three hundred steps in the spiral staircase, and on almost every one of them is a person going up and one going down. To help matters, the light switch is at arm level near the bottom, so the lights go out every minute or so.

There are a lot of Americans kicking around the Hungarian National Gallery, and, oh boy, do they stick out. I'm in the Gothic Statuary section, minding my own business, reflecting on how sinuous and graceful the International Gothic style is when a paif of my fellow countrymen burst through:

"Look! It's another one of the ones from Kassa! Aren't they wonderful?" in the same tone of voice one might use to order a hot dog from the hawker at the ballpark. Fearing the general wrath of the museum guards --

-- Let me interject here the nature of museum guarding in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The ratio of visitors to guards is about one to one, and thus the little old ladies typically feel obliged to follow you around at a distance of about four feet. It's disconcerting, but worse, heaven help the poor visitor who strays from the "recommended" path: the helpful smile comes on and the Finger That Will Brook No Denial (phrase due to K. Paik) emerges, and oh yes, you will turn left when you leave this room, because you do not want to know what happens to those who try to work backwards, or, gasp, skip the section on folk instruments of South Bohemia. Anyway --

-- I leave the room and turn into the Altarpieces room, where, sigh, there are another pair of El Norteamericanos are getting a guided tour. I come in just in time to hear one of them ask the tour guide, "So, you wouldn't happen to find one of these in Dracula's castle, now would you?" Which is just wrong on so many levels that if there were a nearby stake, I'd ignore the reality that we're in HUNGARY rather than ROMANIA and impale him on it. Instead, I sigh and flee into 19th-Century Hungarian Genre Painting.

Back home, Matthew tells me that Canadians sew Canadian flags on their backpacks when travelling, in order to avoid being taken for Americans and hassled. He also explains that Americans have taken to copying the practice -- sewing Canadian flags on their backpages -- which has all the trappings of a perfect Onion story.

Consider the life of a Let's Go researcher. It takes a certain kind of person to travel for two months through iffy countries they've never visited, on $20 a day. It takes a certain self-reliance, a certain tolerance for the unhygenic, a certain ability to make friends with the colorful locals. In short, the person best equipped to make a good Let's Go researcher is perhaps the last person you should trust with your travel recommendations.

Following our guidebook's suggestion, we go to a communist-themed restaurant by the name of Marxim. The neighborhood is not the best, the air is unbelievably smoky, and the place strains at the line between restaurant and dive bar. Of the other people there, some are disturbingly hip, some are just disturbing. We never feel fully comfortable in the place, even with the jokey menu and the "Iron Curtain" decor. The pizza, though, is excellent, perhaps the best of our trip.

A few days later, on our own, late in the evening, we're looking for someplace, any place, to eat. The only open-looking restaurant in our neighborhood is the Nevada Bar, whose outside appearance barely inspires confidence. The inside is decorated with a stereotypical "Western" theme, and I have the best hamburger I've had in years (the burger proper is decent, but the bun is otherworldly). As we eat, a guitarist plays along to a minus-one karaoke tape, performing excellent covers of such classics as "Wit or Witout You" and "Knockin' on Hebbin's Door."

Austria takes its airport security seriously. When I arrive at the airport for my return flight, the terminal has been evacuated while a potential bomb is removed. We cool our heels in the airport shuttle for twenty minutes.

But the guys in jumpsuits and berets aren't done yet. "Your ticket is ready, but they're closing the terminal," the woman behind the counter shouts at me as we are cordoned down to one end of the terminal. Another jumpsuit-clad officer dons a flak vest and drops a piece of baggage into a large and clunky-looking machine and then they're sounding the all-clear. I don't want to think about how loudly the average American business traveler would bawl if subjected such delay.

Not that this is atypical for Vienna. In order to take a synagogue tour, we must present our passports and submit to an interrogation. "Where are you from? You speak Hebrew? Have you ever been to Israel? The Arab states, maybe?" I consider dropping my pants to resolve the issue of my trustworthiness, but fortunately such a step is unnecessary, and the guard waves me through.

That's the Novy Most ("New Bridge") across the Danbue, the oddest suspension bridge I've ever seen. People keep on calling it a UFO, but it looks like the Space Needle to me.

The area right around the Stephansdom is tourist ground zero. This means, in addition to the omnipresent Cambio/Change/Exchange/Weschel booths and shifting eddies of tour groups following their guides like ducklings, a small army of young men in full Mozart mufti: wigs, knee breeches, and long, primary-colored jackets. Their mission: sell you a ticket to a Mozart-Strauss concerts. "57 musicians and four soloists!" proclaims one, as though he were hawking Heinz ketchup. I am seized by the strong desire to kneel down behind one of them, so that Sarah can work the old schoolyard one-two and send him sprawling across my lurking back. For every incongruity there is an equal and opposite indignity.

Have I mentioned how much I hate Baroque art? When you see your second musuem of Baroque art housed in a former Habsburg palace, you understand the true function of art in the Baroque: wallpaper.

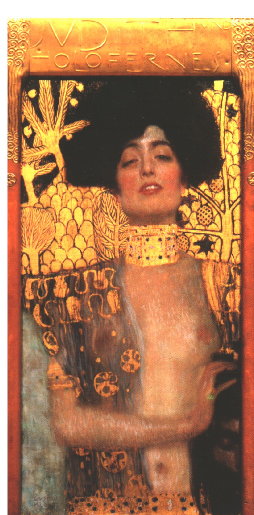

"Pictures of Jesus" is Sarah's term for the endless galleries of competence on display, and while one Crucifixion may inspire wonder, ten Crucifixions inspire laughter, and a hundred inspire only a sense of vague esthetic numbness. After seeing four in a row, I swear to myself that if I see one more Judith with the head of Holofernes, I'm going to yuke.

Apparently, some curator agrees with me, since they've hung Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps in with the passions and the panoramas, and its ferocious tension slices through their gauzy excess like, well, Napoleon through Baroque Europe. In fact, Francis I, Habsburg emperor of Austria (although there known as Francis II, go figure) dissolved the Holy Roman Empire rather than see Napoleon crowned Emperor -- and I like to think of that moment, as much as any other, as the long-awaited and much-needed death-knell for the Baroque.

On our last day in Vienna, we're unexpectedly treated to a protest march coming down Mariahilferstrasse. Apparently, hemp liberation transcends national boundaries. They've got several huge honkin sound trucks, a joint thirty feet long, and, inexplicably, a Hemp Train.

It's a little hard to see in the photos, but a lot of the protesters are wearing Stars of David with the word "Hanf" inside, which strikes me as doubly disturbing. First, there's the inappropriateness of the symbolism, the questionable choice of analogy. All in all, I'm in favor of hemp legalization, but I don't particularly like the hemp legalization movement -- mostly because of this tendency to elevate the issue to the same ethical and political status as genocide (or poverty, human rights, aut al.)

There's also the issue of the consonantal combination "nf." Along with such glorious pairings as "pfl" and "mk" (from "Pimkie," the name of a store we pass several times), it's one of those clusters that's perfectly pronouncable, yet more or less alien to English. In its way, "nf" is stranger than the the profusion of diacritical marks we'll find in Hungary or the Czech "rzh" our guidebook tells us not to even bother trying to pronounce.

We get to Budapest and it's raining, and perhaps this influences our perceptions, but we've definitely crossed from the cheerful West into the post-Communist East. The train station is run-down and dark and filled with sketchy characters offering unlicensed taxi rides. Sarah has been raving about the ultra-quiet Vienna trams (fuel-cell, she guesses), but their Budapest counterparts are loud and obnoxious.

It's the vaguely bombed-out university dorm we're staying in, though, that really strikes me. My room smells of yeast, Sarah's of sewage. Her sink backs up, the hallway lights are mostly out, on our last day, the power gives out entirely. The showers lack nozzles, the toilets are pull-chain and clog up repeatedly, the radiators are exposed and unpainted metal coils.

The only truly fluent English speaker we meet during our six days in Budapest is the sleepy-eyed student who checks us in; we suspect that the "hostel" is a side project of his, a little way to make some money off of vacant rooms. Most of the time, the desk is manned by one of two elderly Hungarian men who spend their time repairing cigarette lighters and seem consistently befuddled by our existence. The students mostly avoid us (and vice-versa), though from the large number of videos they watch on their computers, I'd guess that their Internet bandwidth is pretty good.

We go looking for a laundromat. It doesn't go so well.

We wander through half of Budapest, trying every place listed in both of our guidebooks. Some are empty storefronts, some are no longer laundromats. Our favorite looks a lot like a regular U.S. self-serve laundromat, except that "We tell you which machine to put your clothes in and when." Old habits die hard, apparently.

We finally find a small place, hidden in the back of an unmarked courtyard, in which a squadron of friendly women will individually wash and iron each article of clothing. This isn't exactly what we're looking for, but we've reached the point of Absolute Laundry Crisis, so we run with it.

After that, it's sink-washes for us, with our Alpine Tix detergent, two plastic bags for a washer, and bungee cords for clotheslines. I understand now the function of a washboard, and I also understand what a great boon the washing machine was to the housewives of America.

The fortress-town of Terezin (Theresienstadt) was built in the late 1700s to secure the Habsburg border with the German Empire. During World War II, the Nazis used it as a deportation camp, eventually using it for propaganda purposes, passing it off as a model ghetto where Jews were being happily resettled. In reality, the vast majority of those sent to Terezin were sent, in turn, to the death camps.

In Terezin's Small Fortress is a museum about the history of the fortress. One of the display cases shows a photograph of a vaguely familiar sad sack face. It's Gavrilo Princip, assasin of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and -- the caption explains -- he died in prison in Terezin in 1916.

This is the moment at which the entire trip converges for me. Everything we've seen has pointed ahead to Terezin, and the full horror of the Habsburgs' inadvertent legacy dawns on me as I look at that photo.

The Habsburgs built this town; it was part of the machine of military might that was their empire. And they died here, too, along with the man whose bullet touched off the war that brought down that empire. And then, out of the fragmentary patchwork landscape their collapse left behind, as though on some deadly inverted pilgrimage, the idea of ethnic nationality came back to Terezin with blood in its eyes.

Everything the Habsburgs prided themselves on came here on the trains with the Jews of Prague and Budapest. Centuries of culture and art disembarked with their baggage and filed into the ghetto. And there they were starved, and beaten, and murdered, done in by everything else the Habsburgs left behind.

The pizza in Eastern Europe is surprisingly good. Even in the sketchiest of dives, we're able to get a decent pizza -- although, for unknown reasons, it is considered normal to use corn as a topping, especially on Hawaiian pizza.

They've also got good pastry in this part of the world. Vienna is loaded with chain bakeries that are what ABP wishes it were. In Budapest, every little mom-and-pop grocery has a window facing the street filled with mini pastries. For fifty cents a day, we're eating the breakfast of the gods -- and I never eat breakfast under normal circumstances.

Without even meaning to, I learn how to haggle. Seeing an attractive handmade chess set at a marketplace stall, I look it over and wonder whether I know anyone who'd like it. I'd like to stroll around for a bit and brainstorm my family members' tastes, but the guy will have none of it. He knocks 500 forints off the price and I realize he thinks it's just a bargaining tactic, so I explain, more carefully, that no, I just want to think about who I'd be getting it for.

He stares back at me impassively, as if uncomprehending, which is ridiculous, given the fluidity of his counteroffer and his sales pitch. This annoys me, so I decide to just walk away. "No, thank you" I say, and he pulls those big doe eyes, but as I turn to leave, he calls out to me and knocks another 500 forints off, bringing the price down into the range where I truly do not care about the money, if I can't think of someone who'd like it, I could perfectly well throw the chess set into the trash around the next corner and not mind. So I buy it.

Have I pointed out that the exchange rate is roughly 300 forints to the dollar, making the whole rigamarole an exchange over three dollars? I hate haggling.

Helpful travel tip from me to you: don't go looking for the Museum of Glassblowing in Prague, no matter what your guidebook says. It doesn't exist, and the people at its various alleged locations are getting annoyed by all the people wandering in looking for it.

There are no fat people here. None. The absence of pudge makes itself known as a lacuna, a statistical fluke. We place bets on how long it will be until we see our next genuinely obese person, but after half a day without one, we give up. Once, we think we have spotted one, but he is sporting a fancy camera and shorts, and looks distinctly like every stereotype of an American tourist.

As an even odder counterpoint, Sarah observes that anorexic-looking people are almost equally conspicuous by their absence. The Austrians just seem to have healthy habits -- although, between beer, schnitzel, and the omnipresent bakeries, one would expect every sort of poor dietary practice imaginable.

This turns out to be a specifically Austrian phenomenon: in Budapest, we see plenty of heavyset people (although none who are actively obese) and Sarah is beside herself with joy at the total lack of whippet-thin model-esque bags of bones. Prague is the exact opposite: hyper-thin belts worn loose over pants far too tight to require a belt is the in style, and the matching body type is also in.

The Petrin Gardens in Prague, although they feature some incredible views of the city, also contain the oddest assortment of buildings. There's an observatory, a set of freestanding frescoes illustrating the Stations of the Cross, a miniature replica of the Eiffel Tower, and a mirror maze.

Our first time at the maze, the gate attendants turn us away: it's too late, they're closed for the day. They feign language troubles at our explanations that it won't be their posted last admission time for another five minutes. We come back a few days later, and I'm convinced that "maze" is a mistranslation. "Path" would be more accurate. Defying instructions, I leave a thumbprint on one of the mirrors to express my annoyance.

At the center of the "maze" is a mural of Prague's citizens fighting the Sweedes on Charles Bridge. Betcha didn't know the Sweedes invaded Bohemia; I sure didn't.

Approximately thirty seconds after I take this picture of Prague Castle's ceremonial guards, a man taking a photograph of his family backs directly into them. The leader grunts and spins for a moment, but they don't break stride.

Our hapless hero is wholly unashamed. Damn tourists.

Another recurring theme of the art we see -- or at least, of the art we remember -- is the strong tradition of decoration. Or, more generally, the Eastern Europeans take seriously the "crafts" half of "arts and crafts."

For us, it started in Vienna with Klimt and his Secession (think Art Nouveau, but without quite so many elongated drapey women). Budapest has an Applied Arts museum, mixing an astonishing collection of Seccessionist pieces with illustrative dioramas explaining the technical aspects of the various artistic crafts. Don't show annotated weaving and laceworking samples to a computer person; at least, don't, if you want to have any hope of pulling him away. Only the museum's closing time saved me. Prague's Museum of Decorative Arts is a little less geeky, but has some samples of glassblowing that will blow your mind, along with some Josef Sudek photographs of unearthly beauty and other treasures.

Bratislava's contribution is, in proper style, a little more rough and ready: a crafts exhibition, showing the tools and handiwork of strapmakers and coopers and the other usual crafty suspects. Something about the approach sinks in: material culture of the 16th century starts to take on a reality for me.

I think it's in the connections: those tools on the goldsmith's table came from the blacksmith's forge over there; the letter from the travelling cobbler to his wife about the finances back home refers to a large pot he's bought for her from Mister Pewterer over here. The feel of daily life starts to cohere, and so does the texture of the emerging urban economies.

Something Willard once said to me surfaces in my mind: he wanted to know how more stuff was constructed. A car, say, or a refrigerator: what do they have to do to make one? At the time, I had a ready quip about the pounding machines, the chopping machines, and the extruding machines, but now I'm seeing what a perceptive question "How'd they make that?" is. Klimt got it.

The Original Sacher Torte, as served by the Hotel Sacher, is by no means bad, but the fact remains that in the last century, human progress in the field of chocolate has been quite impressive. And what was state of the art chocolate back in its time is today just another slice of cake on a chipped plate.

Our other remarkable cafe moment comes when we notice a pair of women near us conversing animatedly in sign. Something about their conversation fascinates Sarah; finally she realizes that they are signing in a non-ASL dialect, one whose basic principles differ from those of American Sign Language. Later on on the trip, when we run into an acquaintance from college in Budapest (Dan Biss, for the curious), the smallness of the world will be reaffirmed, but at that moment in a Vienna cafe, it's larger and more wonderful than we'd realized.

In an otherwise rural and unremarkable Budapest suburb one finds a statue park of Soviet-era monuments, preserved in all their outsize glory.

We're trying to get to the park when our ignorance of Hungarian bus protocol leads us to brush up against one of those basic truthes of existence: At all times in life, only a finite number of steps stand between you and utter perdition. At the instant those bus doors close behind us, we're acutely aware that the number for us has just decreased by one -- and also that if we were to walk away from the bus stop, the number would go down by one more.

Nothing more exciting happens: we catch the next bus back to the park, but not before we have entertained visions of knocking on some babushka's door and pantomiming our willingness to do odd chores and supply hard currency in exchange for a place to sleep.

She's about eight, and her parents have brought her to the toy museum. But while their backs are turned, she ignores the display case and goes over to the window. She checks behind her quickly, then leans out over the ledge and spits into the courtyard below.

It's not clear how Eastern Europeans stay hydrated. Restaurants don't serve water, of course, and they're stingy with their beverages: everything comes by the deciliter, and three deciliters is considered a large portion. Further, in a country where prices seem consistently a third or less of what they'd be in the U.S., potable liquids are priced "normally," which is to say, extortionately, compared with everything else. The bottled water, even though close to undrinkable ("It's like fizzy water that's lost its fizz," says Sarah), is similarly expensive. It takes us several days to identify an imported brand which pleases our snobbish palettes.

The juices, though, oh the juices. At every corner shop, at every restaurant, at every food stand in a park, one can buy kindergarten-style juice boxes with straws (or super-sized 3dL boxes) in all sorts of wonderful flavors. Peach and mango are our standbys, but I develop a strong taste for the deliciously thick pear nectar.

When we get to Slovakia, though, there's a nasty surprise waiting for us, as one of the two major local brands of juice is, well, putrid. "Wet dog aftertaste" and "tastes like pork" are Sarah's two comments about the orange juice and there's something about the apple juice that goes where no apple juice should go.

As for the fabled beers of the turf we're travelling through, maybe I don't know enough to get the really good stuff, but I need to summarize my impressions with a large shrug. In Czecho, I try the "original" Budweiser, available in precisely those regions of the world where the American concoction is unavailable, thanks to an ugly trademark lawsuit and its non-compete-clause settlement. And, while it's sad indeed that Bud, that swill you woudln't wish on your enemies, enjoys the massive distribution that it does, the lack of Budvar in this country hardly moves me to tears.

It takes a day or so, but we figure out how the Soviets managed to avoid ruining Bratislava: they put up all their housing projects on the other side of the river.

Vienna has the most effective Holocaust memorial I've ever seen. At first, it looks like a large and blocky tomb; when you get closer, you see that the ridging on the sides is actually row after row of carved books, spines to the inside, numbering in the thousands. The "tomb" is a library, turned inside-out. The People of the Book are represented by books whose titles are forever hidden from view. The doors are permanently sealed, without doorknobs; the inside of this library is a vast empty space, inaccessible, lost.

I have never liked Gustav Klimt's paintings: they remind me too much of the dorm rooms of sentimental freshmen. The Kiss, that monument to decorative passion, has always seemed too much like a substitute for real passion, for real decoration. Seeing it in person has caused me to do a 180: Klimt deserves all the praise he gets. That background really is gold leaf, and seeing it, I finally understand what all those Gothic alterpiece-painters were trying for. Klimt raises the beauty of a decorative painted surface to a new level; you stand there lost in the swirling patterns, colors exploding in your head like a wholly new sense atop the familiar five. I see his Judith I -- head of Holofernes quietly tucked in a corner, almost an afterthought -- and I break my vow.

Hungary was great, once. But the heyday of the Magyar empire was a long time ago, and it seems that old dreams die hard.

Two hundred years on Europe's front lines against the Turks didn't help Hungary's world-historical ambitions; neither did the centuries of Habsburg domination that followed. I hadn't realized how truly non-Hungarian the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy was -- the only times at which the Hungarian monarch was not the same exact person as the Habsburg emperor were when both thrones stood empty. Not that this stopped Hungary from some unpleasant ambitions to dominate Eastern Europe even after their Austrian masters went down to defeat in the Great War.

There's something perverse here, an unwillingness to admit that history makes no promises. Hungarian nationalism has blood on its hands, and most of that blood has been Hungarian.

My seatmate on the flight back is a middle-aged German on his first visit to New York. We're making our descent when he blows my mind. He's got his camcorder out and, he isn't, he can't be, yes he is, he is videotaping the progress map on the video screen, like Uter in a Simpsons episode scripted by Don DeLillo. Not even the announcement to turn off all electronic devices can faze him; he dutifully puts the camcorder away, but a minute later he can't help himself and he's got it out again, taping our landing out the window.

From recent experience, I understand his enthusiasm to be visiting someplace new and exciting. Right now, though, I share that enthusiasm for an entirely different reason. It's good to be home.

You wouldn't think that a murderous Jewish monster made of clay could be turned into a tourist attraction, but Prague is nothing if not resourceful. In the Jewish district, one finds a golem museum, golem-themed tchotchkes, even a Golem restaurant.

Knowing of the Golem of Prague only literarily, I'd always pictured it as human-proportioned, about seven feet tall, and vaguely awkward. The big hulking golems that Prague perfers, though, are, well, uh, er, cuddly. I forgot to take a picture of the best one, so here's some random dude's picture of himself with it:

Where are the golem plush toys? The animated children's movie? Or, for that matter, with the success of The Mummy, why not The Golem? Now there's a more fitting role for The Rock.

Prague's Jewish museum is split across six synagogues. One ticket is good for all six, but on a schedule set by the museum administrators: you will go to the Maisel Synagogue from 11:10 to 11:30, and then you will go to the Spanish Synagogue from 11:40 to 12:00 . . .

By this point -- our fourth Jewish museum -- one collection of ritual artifacts is starting to look very much like another. One can only look at so many shofars before one's eyes glaze over. Prague's collections are a little morbid, since one entire stop on the tour is devoted to artifacts from the Burial Society, whose job apparently sufficiently unpleasant that they felt compelled to commission lots of pictures of themselves to feel a little less grim.

The history exhibits are more interesting: the story of expulsions, confiscations, protections, and backchamber deals is more complex than I can keep track of. It strikes me that the European urban world was never a black-and-white one. If the petty nobility was anti-Semitic, then the emperor might be the protector of the Jews, entirely for the economic power of being their sole patron. No single person had the power to condemn or preserve them; their status depended on mastering their world's complex web of alliances, deals, and antagonisms.

This was the fear that produced the Golem legend. For what is that story but a parable of the frying-pan and the fire? Wish not for power, for power can destroy just as easily as it saves; content yourself with the difficult daily process of moderation and survival.

The thing about Prague is that, at last, they've got real art here. Vienna had good art, but it was the art of empire -- all stolen or commissioned. Budapest and Bratislava had art, sure, but most of it was second-rate genre pictures. Whereas Prague has more good art than it knows what to do with. A sampling of names I liked, reconstructed from my sketchy notes on the back of a hostel reservation fax:

Josef Koudelka's photographs of the 1968 Soviet invasion were so potentially inflammatory he had to publish them anonymously for fear of reprisals, even though he was already in exile by then. The most stunning is of a deserted Wenceslas Square -- a hand with a watch sticks into the frame from the left, as though to emphasize the unnatural quiet.

Karel Pokorny's "Fraternization," ostensibly a monument to the Soviet liberation at the end of World War II, must be seen to be believed: this sculpture of two soldiers embracing can only be described as Socialist Realist gay soft-porn.

Josef Svoboda's stage designs are simple and arresting. Romeo and Juliet gets a colonnade, suspended ten feet in the air, with a single off-center staircase leading up to one of its arches. For a Wagner production, he put static electrical charges on the water droplets in his fog, so the haze would spread out in the way he wanted.

Antonin Prochazka's Cubist paintings use rich color to achieve a sense of balance and calm -- a proof by counterexample that Cubism need not be agitated and kinetic.

Karel Malich's wireframe scultupres are enigmatic and amusing. My favorite might be an eye, or a blob speaking through a trumpet, or maybe a submarine, or lines of magnetic force.

Josef Sudek's photographs through and of rain-streaked windows are considered something close to national treasures.

Karel Nepras makes vaguely human scultures from wires stretched taut like muscle tendons and cones that serve as ambiguous apertures: gaping mouths and screaming ears.

The Sigmund Freud Musuem becomes the site of my worst allergy attack of the trip. My eyes itch so badly that I briefly consider clawing them out; my nose does its best to turn itself inside-out. Given Freud's obsession with the therapeutic value of nasally-administered cocaine, I wonder whether there's something slightly suspicious going on.

Visegrad lacks train service, so to get from there to Bratislava, we must first return to Budapest. We leave an hour and a half of time in between to catch our train, on the theory of "how bad could it get?"

Pretty bad, it turns out. Hungary seems to lack actual highways, and our bus gets stuck in traffic near Budapest's version of Fresh Pond, crawling through an endless procession of traffic lights. We contemplate hopping off and taking the commuter rail the rest of the way in, but just when things look bleakest, the bus muscles its way past one especially brutal merge and we're moving again.

We hit the train station with twenty-five minutes to go -- pant pant no problem pant pant -- only to discover that the signboard has gone out. It's a systemwide failure, apparently, because none of the tracks are marked, either. Sarah's waddling along under her enormous ten-week backpack, so I'm charging around looking for people who look like they might be going to Bratislava and seeing if they know which train is which.

It is under these circumstances that I learn that I can, in a crisis situation, understand spoken German. "Deutsch?" one middle-aged woman asks me and I nod gamely, sure, a little. I don't pick up much more than "abfahrt" and "inland," but suddenly it's crystal-clear, these are the local trains, and those over there are the international ones, and there are intinerary printouts on the doors of the EC trains, and it's all good.

I suppose that this is how mothers who find the strength to lift minivans off of their trapped children must feel.

But this unassuming little tower dates back 700 years and is the oldest building in Prague.

What the Viennese have done to their big-ass cathedral, the Stephansdom, is typical of the city's abject surrender before the conquering armies of tourists. In order to provide a better view from one tower, they've bolted an acrophobia-inducing steel catwalk to the outside of the tower. Up the 200+ steps of the other tower one finds a gift shop.

Underneath the cathedral are the catacombs, and if there isn't already an action-thriller set in Vienna that ends up down there, there ought to be. During various outbreaks of Black Death, Vienna would dig a deep hole in the square next to the Stephansdom and just toss the dead in. Then, for a while, they used the catacombs as inexpensive tomb space. Every time the place filled up, they'd carefully disassemble the skeletons, stack the sorted bones up in neat piles -- femurs with femurs, skulls with skulls -- and free up some space.

Plus, there are some Habsburg emperors and churchmen down there, but they're all resting in nicely sealed stone caskets, which isn't quite as ghoulishly fascinating.

That's the Morava River in the above photo; the far shore is Austrian soil. Supposedly, during the Cold War, the Czechoslovakian government posted sharpshooters in the ruins of Devin Castle to deter border-crossings.

I don't want to talk about the process of buying our train tickets from Bratislava to Prague, other than to say that when it comes to people trying to cut in line in front of you, you're damned if you do and damned if you don't.

The whole experience is a nightmare, and, the next day, on the train, when the conductor informs us that our tickets are good for some trains to Prague, but not for this one, we're not much surprised. We are surprised at how easily the shakedown goes: we don't have any Slovak crowns remaining, but we do have some Austrian shillings. He smiles and asks for a hundred for the two of us, which works out to $3.50 each. No receipt.

We see a dog with dreadlocks, and also an Andean pan-flute band. Those guys are everywhere.

It's raining when we get to Bratislava; it's always raining whenever we arrive anywhere.

There's some confusion at the hostel, due largely to the language barrier. Even with the assistance of a Slovak-speaking colleague in making our reservations, they've got me down as "Graech" in their guest register and when they figure out that "Grimmelmann" is the same thing, they hastily shuffle us from one room to another, before the people who have room 7 reserved show up for real. My attempt to ask for an additional sheet through pantomime is a dismal failure, except for the amusement it affords the man at the desk who wonders why I have put my head down on the counter and am stroking my shoulder.

We've been expecting the absolute worst of post-Communist urbanity -- the sloughed-off detritus of Czechoslovakia, I suppose -- and in the rain, Bratislava looks not only small, but boring and anonymous, too.

Then we turn a few wrong corners, wander into the cobblestones of the Old City, and change our minds. Bratislava is beautiful; it's quiet, too. In Hungary, we were wary and tense much of the time: you know, watch out for onrushing trams, find someplace non-disgusting to eat, figure out the oddities of local street culture. But in Bratislava, everything's easy. Sure, Bratislava has colder weather and a different language, but it has the same organic urban beauty as Padua or Verona. Everything is relaxed and refined, you're basically tripping over good art, and the entire city seems to consist of one extended outdoor cafe filled with happy people.

Plus, they have this cream garlic soup that defies description.

There's no escaping the fact that Bratislava has always been a backwater of Europe. Vienna is Vienna (and Prague will be Prague, when we get to it), and we could see that for a time Budapest was the place to be, but Bratislava has never been anything but a dinky little provincial capital. Not that there's anything wrong with that. But it's best not to go getting ideas.

We go to a few museums that look, in Sarah's immortal phrase, "like the contents of some babushka's attic." The antique clocks and early violins and battered Judaica are all sort of dingy and iffy-looking, and you halfway suspect that that gilt-edged clock from 1746 chimed its last chime in 1752 when the shoddy mainspring gave way.

Part of this, I suppose, you have to chalk up to Slovakia's recent independence: since the Czech Republic got to keep the capital city, it also kept all the museums there. So maybe they did go around to Slovak babushkas, asking them to scour their attics for collectables.

But still, this is a city whose claim to historical fame really is that "Napoleon slept here" (and signed a treaty, too, because he happened to be in the neighborhood). Hungarian nationalism worried me; Slovak nationalism just leaves me mystified. I mean, sure, the Habsburgs had no particular claim to lord it over Bratislava, but I find myself wondering whether there might have been some better bulwark against absolutism than ethnic nationalism.

What looks like the inside of a missile silo is actually the inside of the dome of the Cathedral of St. Isvtan in Budapest.

And then, just when you're most annoyed at someone, they come up with something that makes you stare at them open-mouthed with admiration. Through a barely-marked door in the Slovak National Gallery (they've got the Durer rhino and not much else of note), we cross into a four-floor annex given over to an exhibition on Slovak Action Art.

Denied permission to exhibit and shadowed at every turn by the secret police, a generation of Czech and Slovak artists adapted their art to the conditions of their existence, and the results -- Fluxus' dark Iron Curtain cousins -- are frequently breathtaking.

Jana Zelibska's "Betrothal of Spring," symbolically marrying its participants to the season of rebirth, sounds innocent enough. Until, that is, you compare it with Petr Stembera's attempt to graft a living twig to his arm: despite his exacting attempts to follow proper arboricultural procedures, the twig died. Beneath the expressionless veneer of these happenings lay a despairing scream.

One artist stuffed a copy of Pravda into his mouth, then went to his friends' doors and stood there, unable to talk or even to close his mouth -- after all, it was filled with "truth". Another led discussions in a white shirt bearing a slowly spreading red stain. And another meticulously documented his role-playing "performance" in a national parade, taking himself seriously until he reached the point at which no one could.

That's the joke, of course. This was a country whose leaders have took seriously every grandiose claim made on Art's behalf, to the point of calling out the secret police to make sure it never carried through on those claims. It fell to the artists themselves to frustrate easy meanings; cynical absurdity became a weapon of the powerless.

There's nothing like a (literally) palatial art museum to make you realize that most famous artists are famous for a reason. It's a boring party, lots of saints and crucified Christs gabbing it up, but then your eyes lock with those of a dark mysterious stranger across the room. It's the one Rembrandt in a roomful of unfamiliar names, of course. One of these Madonnas is unlike the others, check the card, yeah, well, that's cause it's a Raphael. There's an exhibit of El Grecos, and they linger in my mind long after most of the pictures of Jesus have faded: El Greco's saints and martyrs have one finger stuck in the light socket, they give you back the energy you've wasted on the excesses all around.

Self-deprecation is the new ethnic humor.

There are many things we could say, and many that we choose not to. There are things we could say about other people, many of them hurtful things, things that good people do not say about each other. Not even to make a joke, although that is always the excuse. It is mutually understood, mutally accepted, that such jokes are not innocent. The assumptions such jokes posit for the sake of their punchline are claims we would not countenance if they were taken seriously, and for this reason the jokes too are forbidden verbal terrain. These are the things that are not said.

But society leaves open certain loopholes, it allows certain exceptions. Disparaging claims made about oneself and the groups to which one belongs, when made in jest, are exempted from this censure. Assume, for the sake of a joke, that I am a resident of a city of idiots. In the punchline, I do something idiotic, and the assumption dies down with the laughter. We are believed not to think of ourselves as idiots, those of us from this city, so the joke arrives, free of any baggage of dangerous implications, and discharges its assumptions and goes about its business.

So it goes with jokes about races and countries, and so also it goes with jokes about groups of one. If I call myself a pathetic specimen of a human being, if I point out my laziness and stupidity, if I tell you about my desparate insecurities, you will laugh until your sides split and then you will give me a stand-up spot, a book deal, an online journal. If I said these same things to you, you would punch me on the spot, unless perhaps you know me well enough to know that I don't mean it. This is the blanket license society grants the self-deprecator: the automatic assumption of insincerity. I can get away with what I say about myself beacuse you know that I don't mean it.

Self-mockery is licensed, and therefore it is also easy. It takes no special courage, it takes no special creativity. It doesn't even require any self-knowledge at all. We are so suffused with the phrases and the posturings of this affected self-loathing that it is no difficult matter to join the crowd. The phrases come readily to the lips, the formulas are easy to master and easy to modulate. Pathos, dysfunction, sloth. Neurosis, idiocy, hapless self-hatred. You can accuse yourself of any of them and joke about it without ever saying anything at all.

So? So we make jokes that don't say anything, so? Jokes are for fun, where is the harm in some gentle self-deprecation?

Here is the harm: every insincere joke at one's own expense devalues the currency of self-criticism that much more. In a crowd of a hundred neuroses laid bare, can you spot the six genuine sufferers, the seven trying to face up to their demons? Whose words express something deeper, and whose are just for show? There is no traction in this landscape of slick sarcasm, there are no handholds left for those who truly need them. When everything is just a joke and nothing more, there is no laughing through tears, there is no laughing so hard that it hurts. One cannot achieve catharsis with store-bought fake rubber vomit. This disingenuous self-mockery makes easy what some people need to be hard.

Here also is the harm: the rhetoric of self-loathing is a trap, an endless stationary spiral staircase. And what you think when you are starting out, and fresh, may not be what you think when you have been climbing past the same scenery for hours. Repetition is reinforcement, and what I tell you three times is true. True, I may start out mocking myself in order to appear humble, I may be looking for an inoffensive way to say something funny, I may adopt your self-mocking style in order to fit in with your culture of perverse one-downmanship -- but perhaps I, and you, will end up by taking seriously all these things we have been assuring ourselves we are not taking seriously. How many times can you tell yourself that you hate your life before you start to believe it? Destroying your sense of self for a joke seems a high price to pay, and yet with this self-mockery, it is the easiest thing in the world.

And here, most of all, is the harm: the rhetoric of jesting self-hatred seems to say something, but it does not. It is risky in the same way that throwing rocks into the polar bear den at the zoo is risky, which is to say, not risky at all. It does nothing to advance one's sense of oneself, but neither does it do anything to advance humanity's understanding of itself. Art produced in this fashion is empty, it says nothing, means nothing, adds nothing. Self-loathing laughter alone is hollow, it has no power of its own anymore, and to pretend that it does is to give the illusion of progress, to distract attention from the places where gains might still be made. Making fun of yourself is easy, and therefore, from an esthetic or an ethical point of view, it is not worth doing.

I am not opposed to self-mockery. I have great empathy with those who struggle with themselves, with their conceptions of themselves, who wonder how they can ever possibly become someone worth being and still remain themselves. Their struggle is hard enough without having to deal with sarcastic hecklers who carry out elaborate parodies of their sufferings.

Neither do I think that jokes at one's own expense are unfunny. I laugh at them, and sometimes I make them. But I have no illusions that they are anything more than cheap laughs, jokes of the sort one can crank out endlessly because the patterns are so reliable, so unchanging. It's the game of knock-knock jokes with more complicated rules.

And neither do I believe that self-examination and penetrating laughter have no place in human and artistic development. They are tools, techniques, materials, and they can be profitably employed together. But they do not suffice by themselves, they are not enough, we're exhausted the possibilities here. They must be harnessed to new ideas, to to other possibilities, they must be broken down and recombined and launched out upon the world in forms not seen before. A joke about myself, that's old hat. But a joke about myself with a twist in it, with a sudden jumping-off into a rabbit-hole uncovered during the first laugh, this is worth paying attention to, this is worth doing. The poetics of personal failure have failed. We msut make them work again.

One must go further than simply making fun of oneself, one must go further.

Hungarian museums are distinguished not so much by the quality of their collections (which range from awful to excellent, same as any country's) as by the audacity of their curators. The National Museum has an exhibit on 19th-century metal laurel wreaths, together with a long descriptive text about the political and ideological implications of calling artists "immortal" in their own lifetimes. When it works, it's wonderful: an exhibit on the 1956 rebellion juxtaposes a recreation of the office of the head of the secret police with a recreation of a prison-camp cell. And when it doesn't work, well, it's still kind of impressive to see see a museum devote eight display cases to proving that Hungary's ceremonial crown was built at one time (rather than being glued together from two distinct crowns).

The grand prize for ambition, though, goes to the Museum of Ethnography, which has supplemented a costumes-n-tools permanent exhibition with a temporary show entitled "Images of Time," which gives the impression of being the final class projects of a bunch of brash young curatorial students told to "make a room that explains time." "Musical Time" explores musical notation as a system for illustrating time; "Timeless Time" explains itself by means of Zen Buddhist artifacts. It gets better. "The Museum as Time Machine" is just what it sounds like, whereas "The Timelessness of Confinement" compares monasteries to prisons in their relation to time. One room lays out Mexican popular devotional altars (candles, icons, Corona bottles), another traces the "transitional time" of a Berber wedding ceremony, and the final room is devoted to gambling and board games as techniques for predicting the future.

It seems to me, perhaps, that fifty years of creativity and conversation have been not so much suppressed as bottled up, and that Hungary's curators, as the keepers of their country's intellectual tradition, are trying to make up for lost time, as it were.